Crypto-monnaie décentralisée

| Bitcoin | |

|---|---|

Logo Bitcoin préventif | |

| dénominations | |

| nombreuses | Bitcoins |

| symbole | ₿ (Unicode: U + 20BF ₿ SIGNE BITCOIN (HTML ₿))[a] |

| Symbole de téléscripteur | BTC, XBT[b] |

| Précision | dix-8 |

| sous-unités | |

| 1/1000 | millibitcoin |

| 1/100000000 | Satoshi[2] |

| Développement | |

| Auteur d’origine | Satoshi Nakamoto |

| papier blanc | « Bitcoin: un système de paiement électronique à égalité »[4] |

| Implémentation (s) | Bitcoin Core |

| Édition introductive | 0.1.0 / 9 janvier 2009 |

| Dernière version | 0.19.1 / 9 mars 2020[3] |

| Statut de développement | actif |

| Site Internet | bitcoin |

| registre | |

| Le guide commence | 3 janvier 2009 |

| Tidstämplingsschema | Preuve de travail (inversion de hachage partielle) |

| La fonction de hachage | SHA-256 |

| calendrier de publication | Décentralisé (récompense en bloc) Initialement ₿50 par bloc, divisé par deux tous les 210 000 blocs[8][9] |

| Récompense de blocage | ₿6,25[c] |

| Temps de blocage | 10 minutes |

| Explorateur de blocs | bitaps |

| Alimentation en circulation | 18355100 ₿ (au 1er mai 2020[update]) |

| Limite de livraison | ,00021,000,000[5][d] |

| |

Bitcoin[a] (₿) est une crypto-monnaie. Il s’agit d’une monnaie numérique décentralisée sans banque centrale ni administrateur unique qui peut être envoyée d’un utilisateur à l’autre sur le réseau Bitcoin peer-to-peer sans avoir besoin d’intermédiaires.[8]

Les transactions sont vérifiées par des nœuds de réseau via la cryptographie et enregistrées dans un registre distribué publiquement appelé blockchain. Le Bitcoin a été inventé en 2008 par une personne inconnue ou un groupe de personnes nommé Satoshi Nakamoto[15] et a commencé en 2009[16] lorsque son code source a été publié en open source.[7]:ch. 1 Les bitcoins sont créés en récompense d’un processus connu sous le nom de minage. Ils peuvent être échangés contre d’autres devises, produits et services.[17] Une recherche réalisée par l’Université de Cambridge estime qu’en 2017, 2,9 à 5,8 millions d’utilisateurs uniques utilisaient un portefeuille de crypto-monnaie, la plupart utilisant du bitcoin.[18]

Le Bitcoin a été salué et critiqué. Les critiques ont noté son utilisation dans les transactions illégales, sa forte consommation d’électricité, la volatilité des prix et le vol de stock. Certains économistes, dont plusieurs lauréats du prix Nobel, l’ont qualifié de bulle spéculative. Le bitcoin a également été utilisé comme investissement, bien que plusieurs régulateurs aient émis des avertissements d’investissement concernant le bitcoin.[19][20]

Histoire

Créer

Le nom de domaine « bitcoin.org » a été enregistré le 18 août 2008.[21] Le 31 octobre 2008, un lien vers un article rédigé par Satoshi Nakamoto avec le titre Bitcoin: un système de paiement électronique peer-to-peer[4] a été publié sur une liste de diffusion cryptographique.[22] Nakamoto a implémenté le logiciel bitcoin en open source et l’a publié en janvier 2009.[23][24][16] L’identité de Nakamoto reste inconnue.[15]

Le 3 janvier 2009, le réseau bitcoin a été créé lorsque Nakamoto a cassé le premier bloc de la chaîne, connu sous le nom de bloc de genèse.[25][26] Dans la base de pièces de monnaie de ce bloc se trouvait le texte « Le Chancelier Times 03 / Jan / 2009 au bord d’un autre défi pour les banques ».[16] Cette note fait référence à un titre publié par Les temps et a été interprété à la fois comme un horodatage et un commentaire sur l’instabilité causée par la banque de réserves fractionnaires.[27]:18

Le destinataire de la première transaction bitcoin était cypherpunk Hal Finney, qui a créé le premier système de preuve de travail réutilisable (RPoW) en 2004.[28] Finney a téléchargé le logiciel bitcoin à la date de sortie et le 12 janvier 2009 a reçu dix bitcoins de Nakamoto.[29][30] Les autres premiers supporters de Cypherpunk étaient les créateurs de prédécesseurs de Bitcoin: Wei Dai, créateur de b-money, et Nick Szabo, créateur de Bit Gold.[25] En 2010, la première transaction commerciale connue avec le bitcoin a eu lieu lorsque le programmeur Laszlo Hanyecz a acheté deux pizzas Papa Johns pour 10 000 000.[31]

Les analystes de Blockchain estiment que Nakamoto a extrait environ un million de bitcoins[32] avant de disparaître en 2010, lorsqu’il a remis la clé réseau et le contrôle du référentiel de codes à Gavin Andresen. Andresen est devenu plus tard le principal développeur de la Fondation Bitcoin.[33][34] Andresen a ensuite tenté de décentraliser le contrôle. Cela a permis à la controverse de se développer sur la voie future du bitcoin, contrairement à l’autorité perçue dans la contribution de Nakamoto.[35][34]

2011-2012

Après les premières transactions de «preuve de concept», les premiers grands utilisateurs du bitcoin ont été les marchés noirs, comme Silk Road. Au cours de ses 30 mois d’existence, qui ont commencé en février 2011, Silk Road a exclusivement accepté les bitcoins comme moyen de paiement et a effectué 9,9 millions de bitcoins, d’une valeur d’environ 214 millions de dollars.[36]:222

En 2011, le prix de 0,30 $ par bitcoin a commencé à grimper à 5,27 $ pour l’année. Le prix est passé à 31,50 $ le 8 juin. En un mois, le prix est tombé à 11,00 $. Le mois prochain, il est tombé à 7,80 $ et un autre mois à 4,77 $.[37]

Le litecoin, une spin-off ou un altcoin précoce du Bitcoin, est apparu en octobre 2011.[38] De nombreux altcoins ont été créés depuis.[39]

En 2012, le prix du bitcoin de 5,27 $ a commencé à grimper à 13,30 $ pour l’année.[37] Le 9 janvier, le prix était passé à 7,38 $, mais a ensuite chuté de 49% à 3,80 $ au cours des 16 prochains jours. Le prix est ensuite passé à 16,41 $ le 17 août, mais a chuté de 57% à 7,10 $ au cours des trois prochains jours.[40]

La Fondation Bitcoin a été fondée en septembre 2012 pour promouvoir le développement et l’utilisation du bitcoin.[41]

2013-2016

En 2013, les prix ont commencé à augmenter de 13,30 $ à 770 $ le 1er janvier 2014.[37]

En mars 2013, la blockchain a été temporairement divisée en deux chaînes indépendantes avec des règles différentes en raison d’une erreur dans la version 0.8 du logiciel bitcoin. Les deux blockchains ont travaillé simultanément pendant six heures, chacune avec sa propre version de l’historique des transactions de la scission. Le fonctionnement normal a été restauré lorsque la majorité du réseau a été rétrogradé à la version 0.7 du logiciel bitcoin et a sélectionné la version blockchain rétrocompatible. En conséquence, cette blockchain est devenue la chaîne la plus longue et pourrait être acceptée par tous les participants, quelle que soit leur version du logiciel bitcoin.[42] Pendant la scission, le mont. La bourse Gox a arrêté les dépôts de bitcoins courts et le prix a chuté de 23% à 37 $[42][43] avant de revenir à un niveau précédent d’environ 48 $ dans les heures suivantes.[44]

Le réseau américain des délits financiers (FinCEN) a établi des directives réglementaires pour les « monnaies virtuelles décentralisées » telles que le bitcoin, classant les mineurs de bitcoins américains qui vendent leurs bitcoins générés comme des entreprises de services monétaires (MSB), qui sont soumis à l’enregistrement ou à d’autres obligations légales.[45][47]

En avril, BitInstant et Mt. Gox a subi des retards de traitement en raison d’une capacité insuffisante[48] entraînant une chute du prix du bitcoin de 266 $ à 76 $ avant de revenir à 160 $ en six heures.[49] Le prix du bitcoin est passé à 259 $ le 10 avril, mais s’est ensuite écrasé de 83% à 45 $ au cours des trois prochains jours.[40]

Le 15 mai 2013, les autorités américaines ont saisi des comptes concernant le mont. Gox après avoir découvert qu’il n’avait pas été enregistré comme émetteur d’argent auprès de FinCEN aux États-Unis.[50][51] Le 23 juin 2013, la Drug Enforcement Administration des États-Unis a indiqué que le ₿11.02 était un bien saisi dans une notification du Département de la justice des États-Unis en vertu de la loi américaine 21 U.S.C. § 881. C’était la première fois qu’une autorité prenait du bitcoin.[52] Le FBI a arrêté environ 30 000 personnes[53] en octobre 2013 depuis le site sombre Silk Road lors de l’arrestation de Ross William Ulbricht.[54][55][56] Ces bitcoins ont été vendus lors d’une vente aux enchères à l’aveugle par le United States Marshals Service à l’investisseur en capital-risque Tim Draper.[53] Le prix du Bitcoin est passé à 755 $ le 19 novembre, passant de 50% à 378 $ le même jour. Le 30 novembre 2013, le prix a atteint 1163 $ avant le début d’un crash à long terme et a chuté de 87% à 152 $ en janvier 2015.[40]

Le 5 décembre 2013, la Banque populaire de Chine a interdit aux institutions financières chinoises d’utiliser des bitcoins.[57] Après l’annonce, la valeur des bitcoins a chuté,[58] et Baidu n’acceptait plus les bitcoins pour certains services.[59] L’achat de biens immobiliers avec n’importe quelle monnaie virtuelle était illégal en Chine depuis au moins 2009.[60]

En 2014, les prix ont commencé à 770 $ et sont tombés à 314 $ pour l’année.[37] Le 30 juillet 2014, la Fondation Wikimedia a commencé à accepter les dons de bitcoins.[61]

En 2015, les prix ont commencé à 314 $ et ont atteint 434 $ pour l’année. En 2016, les prix ont augmenté et ont atteint 998 $ le 1er janvier 2017.[37]

2017-2019

Le 15 juillet 2017, le témoin ségrégué controversé [SegWit] la mise à niveau du logiciel a été approuvée (« verrouillée »). Segwit était destiné à prendre en charge Lightning Network et à améliorer l’évolutivité.[62] SegWit a ensuite été activé sur le réseau le 24 août 2017. Le prix du Bitcoin a augmenté de près de 50% la semaine après l’approbation de SegWit.[62] Le 21 juillet 2017, le bitcoin s’échangeait à 2748 $, en hausse de 52% par rapport au 14 juillet 2017: 1835 $.[62] La prise en charge des gros blocs qui n’étaient pas satisfaits de l’activation de SegWit a forgé le logiciel le 1er août 2017 pour créer Bitcoin Cash.

Les prix ont commencé à 998 $ en 2017 et ont atteint 13 412,44 $ le 1er janvier 2018,[37] après avoir atteint son heure de pointe de 19783,06 $ le 17 décembre 2017.[63]

La Chine a interdit le commerce de bitcoins, les premières mesures ont été prises en septembre 2017 et une interdiction totale à compter du 1er février 2018. Les prix du bitcoin sont ensuite passés de 9052 $ à 6914 $ le 5 février 2018.[40] Le pourcentage de trading de bitcoins dans le renminbi chinois est passé de plus de 90% en septembre 2017 à moins de 1% en juin 2018.[64]

Pendant le reste du premier semestre 2018, le prix du bitcoin a varié de 11 480 $ à 5 848 $. Le 1er juillet 2018, le prix du bitcoin était de 6343 $.[65][66] Le prix au 1er janvier 2019 était de 3747 $, en baisse de 72% pour 2018 et de 81% depuis lors.[65][67]

Les prix du Bitcoin ont été négativement affectés par plusieurs piratages ou vols dans les échanges de crypto-monnaies, notamment les vols de Coincheck en janvier 2018, Coinrail et Bithumb en juin et Bancor en juillet. Pour les six premiers mois de 2018, des valeurs de 761 millions de dollars de crypto-monnaies volées aux bourses ont été signalées.[68] Le prix du Bitcoin a également été affecté si d’autres crypto-monnaies étaient négociées en devises sur Coinrail et Bancor, les investisseurs étant préoccupés par la sécurité des échanges de crypto-monnaies.[69][70][71] En septembre 2019, l’Intercontinental Exchange (propriétaire de NYSE) a commencé à négocier des contrats à terme sur bitcoins sur son échange appelé Bakkt.[72] Bakkt a également annoncé qu’il lancerait des options sur le bitcoin en décembre 2019.[73] En décembre 2019, YouTube a supprimé les vidéos de bitcoin et de crypto-monnaie, mais a ensuite restauré le contenu et a déclaré avoir « fait une erreur ».[74]

En février 2019, la bourse de crypto-monnaie canadienne Quadriga Fintech Solutions a échoué avec environ 200 millions de dollars manquants.[75] En juin 2019, le prix était revenu à 13000 $.[76]

2020

Selon CoinMetrics et Forbes, le 11 mars, 281 000 bitcoins ont été vendus par des propriétaires qui les détenaient pendant trente jours seulement. Cela se compare à 4311 bitcoins qui étaient en sommeil depuis un an ou plus, ce qui suggère que la grande majorité de la volatilité du bitcoin ce jour-là provenait d’un achat récent.[76] Au cours de la semaine du 11 mars 2020, à la suite de l’échange de crypto-monnaie pandémique COVID-19, Kraken a connu une augmentation de 83% du nombre d’inscriptions de compte au cours de la semaine suivant l’effondrement du prix du bitcoin, résultat de la décision des acheteurs de profiter du prix bas.[76]

Conception

Unités et divisibilité

L’unité de compte pour le système bitcoin est une bitcoin. Les symboles boursiers utilisés pour représenter le bitcoin sont BTC[b] et XBT.[c][81]:2 Son caractère Unicode est ₿.[1] Les petites quantités de bitcoin utilisées comme dispositifs alternatifs sont le millibitcoin (mBTC) et Satoshi (Saturé). Nommé en hommage au créateur du bitcoin, un Satoshi est la plus petite quantité de bitcoin qui représente 0,00000001 des bitcoins, des centaines de millions de bitcoins.[2] Un millibitcoin est égal 0,001 Bitcoins; mille bitcoins ou 100 000 satoshis.[82]

chaîne de bloc

La blockchain Bitcoin est un livre public qui enregistre les transactions bitcoin.[85] Il est mis en œuvre comme une chaîne de bloquer, chaque bloc contenant un hachage du bloc précédent jusqu’au bloc de gènes[d] de la chaîne. Un réseau de nœuds de communication exécutant un logiciel bitcoin gère la blockchain.[36]:215-219 Transactions du formulaire le payeur X envoie Y bitcoins au bénéficiaire Z est transmis à ce réseau avec des applications logicielles facilement accessibles.

Les nœuds de réseau peuvent valider des transactions, les ajouter à leur copie du grand livre, puis envoyer ces extensions de grand livre à d’autres nœuds. Pour réaliser une vérification indépendante de la chaîne propriétaire, chaque nœud de réseau stocke sa propre copie de la chaîne de blocs.[86] Avec des intervalles de temps variables en moyenne toutes les dix minutes, un nouveau groupe de transactions acceptées, appelé bloc, est créé, ajouté à la blockchain et rapidement publié sur tous les nœuds sans nécessiter de surveillance centrale. Cela permet au logiciel bitcoin de déterminer quand un bitcoin particulier a été dépensé, ce qui est nécessaire pour éviter les dépenses doubles. Un registre conventionnel enregistre les transferts de factures ou de débentures réelles qui existent en dehors de celui-ci, mais la blockchain est le seul endroit où les bitcoins peuvent être considérés comme sous la forme de résultats inutilisés de transactions.[7]:ch. 5

transactions

Les transactions sont définies à l’aide d’un langage de script de type Forth.[7]:ch. 5 Les transactions consistent en un ou plusieurs contributions et un ou plusieurs les sorties. Lorsqu’un utilisateur envoie des bitcoins, l’utilisateur spécifie chaque adresse et quantité de bitcoins envoyés à cette adresse dans une sortie. Pour éviter les dépenses en double, chaque entrée doit faire référence à une sortie précédemment inutilisée dans la blockchain.[87] L’utilisation de plusieurs entrées correspond à l’utilisation de plusieurs pièces dans une transaction en espèces. Étant donné que les transactions peuvent avoir plusieurs sorties, les utilisateurs peuvent envoyer des bitcoins à plusieurs destinataires dans une transaction. Comme dans une transaction en espèces, la somme des biens en entrée (pièces utilisées pour payer) peut dépasser le montant prévu des paiements. Dans un tel cas, une sortie supplémentaire est utilisée qui renvoie la modification au payeur.[87] N’importe quelle entrée satoshis les frais de transaction ne seront pas signalés dans les résultats de transaction.[87]

les frais de transaction

Bien que les frais de transaction soient facultatifs, les mineurs peuvent choisir les transactions à traiter et prioriser ceux qui paient des frais plus élevés.[87] Les mineurs peuvent choisir des transactions en fonction des frais payés par rapport à leur taille de stockage, et non du montant absolu payé en tant que frais. Ces frais sont généralement mesurés en satoshis par octet (sat / b). La taille des transactions dépend du nombre d’entrées utilisées pour créer la transaction et du nombre de sorties.[7]:ch. 8

La possession

La blockchain enregistre des bitcoins dans des adresses bitcoin. La création d’une adresse Bitcoin ne nécessite rien de plus que de choisir une clé privée valide aléatoire et de calculer l’adresse Bitcoin correspondante. Ce calcul peut être effectué en une fraction de seconde. Mais l’inverse, pour calculer la clé privée pour une adresse bitcoin donnée, est pratiquement impossible.[7]:ch. 4 Les utilisateurs peuvent en informer d’autres ou publier une adresse bitcoin sans compromettre la clé privée correspondante. De plus, le nombre de clés privées valides est si important qu’il est extrêmement peu probable que quelqu’un calcule une paire de clés déjà utilisée et disposant de fonds. Le grand nombre de clés privées valides rend impossible l’utilisation de la force brute pour compromettre une clé privée. Afin de dépenser leurs bitcoins, le propriétaire doit connaître la clé privée correspondante et signer numériquement la transaction. Le réseau vérifie la signature avec la clé publique. la clé privée n’est jamais divulguée.[7]:ch. 5

Si la clé privée est perdue, le réseau bitcoin ne reconnaîtra aucune preuve de propriété;[36] Les pièces sont alors inutilisables et se perdent efficacement. Par exemple, en 2013, un utilisateur a déclaré avoir perdu 7 500 bitcoins, d’une valeur de 7,5 millions de dollars à l’époque, lorsqu’il a accidentellement jeté un disque dur contenant sa clé privée.[88] On pense qu’environ 20% de tous les bitcoins sont perdus. Ils auraient une valeur marchande d’environ 20 milliards de dollars aux prix en juillet 2018.[89]

Pour garantir la sécurité des bitcoins, la clé privée doit être gardée secrète.[7]:ch. dix Si la clé privée est divulguée à un tiers, par exemple grâce à une violation de données, des tiers peuvent l’utiliser pour voler tous les bitcoins associés.[90] En décembre 2017[update], environ 980 000 bitcoins ont été volés dans les échanges de crypto-monnaie.[91]

En termes de répartition de la propriété, le 16 mars 2018, 0,5% des portefeuilles bitcoin détiennent 87% de tous les bitcoins jamais éclatés.[92]

Accent

Accent est un service de tenue de dossiers qui se fait grâce à l’utilisation de la puissance de traitement informatique.[f] Les mineurs gardent la blockchain cohérente, complète et inchangée en regroupant à plusieurs reprises les transactions nouvellement émises en une seule bloquer, qui est ensuite transmis au réseau et vérifié par les nœuds récepteurs.[85] Chaque bloc contient un hachage cryptographique SHA-256 du bloc précédent,[85] il est donc lié au bloc précédent et donne son nom à la blockchain.[7]:ch. 7[85]

Pour être accepté par le reste du réseau, un nouveau bloc doit contenir un preuve de travail (POW).[85] Le système utilisé est basé sur le système anti-spam d’Adam Back de 1997, Hashcash.[96][[[[vérification infructueuse][4] PoW oblige les mineurs à trouver un numéro appelé nonce, de sorte que lorsque le contenu du bloc est haché avec nonce, le résultat est numériquement inférieur à la cible de difficulté du réseau.[7]:ch. 8 Cette preuve est facile à vérifier pour tous les nœuds du réseau, mais extrêmement longue à générer, comme pour un hachage cryptographique sécurisé, les mineurs doivent essayer de nombreuses valeurs nonce différentes (généralement la séquence de valeurs testées augmente les nombres naturels: 0, 1, 2, 3, …[7]:ch. 8) avant d’atteindre l’objectif de difficulté.

Chaque 2,016 blocs (environ 14 jours avec environ 10 minutes par bloc) ajuste la cible de difficulté en fonction des dernières performances du réseau, dans le but de maintenir le temps moyen entre les nouveaux blocs de dix minutes. De cette façon, le système s’adapte automatiquement à la quantité totale d’énergie minière dans le réseau.[7]:ch. 8 Entre le 1er mars 2014 et le 1er mars 2015, le nombre moyen de mineurs devrait essayer avant la création d’un nouveau bloc de 16,4 quintillions à 200,5 quintillions.[97]

Le système de preuve de travail, associé au blocage de blocs, rend les modifications de la chaîne de blocs extrêmement difficiles, car un attaquant doit modifier tous les blocs suivants pour que les modifications apportées à un bloc soient acceptées.[98] Lorsque de nouveaux blocs sont constamment cassés, la difficulté de modifier un bloc augmente avec le temps et le nombre de blocs suivants (également appelé confirmations du bloc donné) augmente.[85]

La fourniture

Le mineur à succès qui trouve le nouveau bloc est autorisé par le reste du réseau à se récompenser avec des bitcoins nouvellement créés et des frais de transaction.[99] Au 11 mai 2020[update],[100] la récompense était de 6,25 bitcoins nouvellement créés par bloc ajoutés à la blockchain, plus les frais de transaction des paiements traités par le bloc. Pour réclamer la récompense, une transaction spéciale est appelée Coinbase inclus dans les paiements traités.[7]:ch. 8 Tous les bitcoins existants ont été créés dans de telles transactions de base de pièces. Le protocole Bitcoin stipule que la récompense pour l’ajout d’un bloc sera réduite de moitié tous les 210 000 blocs (environ tous les quatre ans). Finalement, les récompenses diminueront à zéro et la limite de 21 millions de bitcoins[g] sera atteint c. 2140; l’inscription ne sera alors récompensée que par des frais de transaction.[101]

En d’autres termes, Nakamoto a établi une politique monétaire basée sur la rareté artificielle lorsque le bitcoin a commencé, le nombre total de bitcoins ne pouvant jamais dépasser 21 millions. De nouveaux bitcoins sont créés toutes les dix minutes environ et le rythme auquel ils sont générés diminue d’environ la moitié tous les quatre ans jusqu’à ce qu’ils soient tous en circulation.[102]

Exploitation minière en commun

La puissance informatique est souvent mise en commun ou «mise en commun» pour réduire la variation des revenus miniers. Les plates-formes minières individuelles doivent souvent attendre de longues périodes pour confirmer un bloc de transactions et recevoir le paiement. Dans un pool, tous les mineurs participants sont payés chaque fois qu’un serveur participant résout un blocage. Ce paiement dépend de la quantité de travail qu’un mineur a contribué à trouver ce bloc.[103]

Portefeuilles

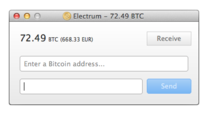

Electrum, un client simple

UNE portefeuille stocke les informations nécessaires aux transactions de bitcoins. Alors que les portefeuilles sont souvent décrits comme un endroit à garder[104] ou stocker des bitcoins, en raison de la nature du système, les bitcoins sont inséparables du registre des transactions de la blockchain. Un portefeuille est plus précisément défini comme quelque chose qui « stocke les informations d’identification numériques pour vos avoirs en bitcoins » et vous permet d’y accéder (et de les dépenser).[7]:ch. 1, glossaire Bitcoin utilise la cryptographie à clé publique, où deux clés cryptographiques, une publique et une privée, sont générées.[105] À sa base, un portefeuille est une collection de ces clés.

Il existe plusieurs situations dans lesquelles les portefeuilles peuvent fonctionner. Ils ont une relation inverse en ce qui concerne les exigences de confiance et de calcul.

- Clients complets vérifier les transactions directement en téléchargeant une copie complète de la blockchain (plus de 150 Go en janvier 2018)[update]).[106] Ils sont le moyen le plus sûr et le plus fiable d’utiliser le réseau car la confiance des tiers n’est pas requise. Les clients complets contrôlent les blocs valides qui sont rompus et les empêchent d’agir sur une chaîne qui rompt ou modifie les règles du réseau.[7]:ch. 1 En raison de sa taille et de sa complexité, le téléchargement et la vérification de l’ensemble de la blockchain ne conviennent pas à tous les appareils informatiques.

- Clients légers consulter des clients complets pour envoyer et recevoir des transactions sans avoir besoin d’une copie locale de l’ensemble de la blockchain (voir vérification de paiement simplifiée – SPV). Cela rend les clients légers beaucoup plus rapides à installer et leur permet d’être utilisés sur des appareils à faible consommation et à faible bande passante comme les smartphones. Cependant, lors de l’utilisation d’un portefeuille léger, l’utilisateur doit s’appuyer sur le serveur dans une certaine mesure, car il peut renvoyer des valeurs incorrectes à l’utilisateur. Les clients légers suivent la blockchain la plus longue et ne s’assurent pas qu’elle est valide, ce qui nécessite la confiance des mineurs.[107]

Services Internet tiers appelés portefeuilles en ligne offre des fonctionnalités similaires mais peut être plus facile à utiliser. Dans ce cas, les références sont stockées pour accéder à l’argent du fournisseur de portefeuilles en ligne plutôt que sur le matériel de l’utilisateur.[108] En conséquence, l’utilisateur doit avoir pleinement confiance dans le fournisseur de portefeuilles en ligne. Un fournisseur malveillant ou une violation de sécurité du serveur peut entraîner le vol de bitcoins de confiance. Un exemple d’une telle faille de sécurité s’est produite avec le mont. Gox 2011.[109]

Portefeuilles physiques

Un portefeuille en papier avec l’adresse visible pour ajouter ou vérifier les fonds stockés. La partie de la page qui contient la clé privée est repliée et scellée.

Portefeuilles physiques stocker les informations nécessaires pour dépenser des bitcoins hors ligne et peut être aussi simple qu’une copie papier de la clé privée:[7]:ch. dix une portefeuille en papier. Un portefeuille en papier est créé avec une paire de clés générées sur un ordinateur sans connexion Internet; la clé privée est imprimée ou imprimée sur le papier[h] puis supprimé de l’ordinateur. Le portefeuille papier peut ensuite être stocké dans un emplacement physique sécurisé pour un téléchargement ultérieur. Les bitcoins stockés avec un portefeuille en papier seraient chambre froide.[110]:39

Cameron et Tyler Winklevoss, fondateurs de la bourse Gemini Trust Co., ont rapporté qu’ils avaient coupé leur portefeuille en papier en morceaux et les avaient stockés dans des enveloppes distribuées dans des coffres-forts à travers les États-Unis.[111] Grâce à ce système, le vol d’une enveloppe ne permettrait pas au voleur de voler des bitcoins ou de priver les propriétaires légitimes de leur accès.[112]

Les portefeuilles physiques peuvent également prendre la forme de pièces métalliques[113] avec une clé privée disponible sous un hologramme de sécurité dans une niche à l’arrière.[114]:38 L’hologramme de sécurité est détruit lorsqu’il est supprimé du jeton, indiquant que la clé privée a été atteinte.[115] À l’origine, ces symboles étaient frappés dans le laiton et d’autres métaux communs, mais ont ensuite utilisé des métaux précieux à mesure que le bitcoin gagnait en valeur et en popularité.[114]:80 Des pièces dont la valeur nominale stockée peut atteindre 1 000 have ont été libérées en or.[114]:102-104 La collection de pièces du British Museum contient quatre spécimens de la première série[114]:83 de jetons Bitcoin financés; une est actuellement exposée dans la galerie d’argent du musée.[116] En 2013, un fabricant Utahn de ces jetons a été ordonné par le Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) de s’enregistrer en tant qu’entreprise de services monétaires avant de produire des jetons Bitcoin plus financés.[113][114]:80

Un autre type de portefeuille physique appelé portefeuille matériel garde les références hors ligne tout en facilitant les transactions.[117] Le portefeuille matériel agit comme un équipement informatique et signe les transactions à la demande de l’utilisateur, qui doit appuyer sur un bouton du portefeuille pour confirmer qu’il avait l’intention d’effectuer la transaction. Les portefeuilles matériels n’exposent jamais leurs clés privées et conservent les bitcoins dans les entrepôts frigorifiques même s’ils sont utilisés avec des ordinateurs qui peuvent être compromis par des logiciels malveillants.[110]:42-45

implémentations

Le premier programme de portefeuille, simplement nommé Bitcoin, et parfois appelé Client Satoshi, publié en 2009 par Satoshi Nakamoto en tant que logiciel open source.[16] Dans la version 0.5, le client est passé de la boîte à outils de l’interface utilisateur de wxWidget à Qt, et le package entier a été appelé comme Bitcoin Qt.[118] Après la sortie de la version 0.9, le progiciel a été renommé Bitcoin Core différer du réseau sous-jacent.[119][120]

Fourches

Bitcoin Core est peut-être l’implémentation ou le client le plus connu. Il existe des clients alternatifs (fourches Bitcoin Core), tels que Bitcoin XT, Bitcoin Unlimited,[35] et Bitcoin parité.[121]

Le 1er août 2017, un hard fork de bitcoin, connu sous le nom de Bitcoin Cash, a été créé.[122] Bitcoin Cash a une limite de taille de bloc plus grande et avait une blockchain identique au moment de la fourchette. Le 24 octobre 2017, un autre hard fork, Bitcoin Gold, a été créé. Bitcoin Gold modifie l’algorithme de preuve d’utilisation utilisé dans le minage, car les développeurs pensaient que le minage était devenu trop spécialisé.[123]

Décentralisation

Le Bitcoin est décentralisé:[8]

- Le Bitcoin n’a pas d’autorité centrale.[8]

- Il n’y a pas de serveur central; Le réseau bitcoin est peer-to-peer.[16]

- Il n’y a pas de stockage central; Le livre Bitcoin est distribué.[124]

- La gestion est publique; n’importe qui peut le stocker sur son ordinateur.[7]:ch. 1

- Il n’y a pas d’administrateur unique;[8] le livre est tenu par un réseau de mineurs également privilégiés.[7]:ch. 1

- N’importe qui peut devenir mineur.[7]:ch. 1

- The additions to the ledger are maintained through competition. Until a new block is added to the ledger, it is not known which miner will create the block.[7]:ch. 1

- The issuance of bitcoins is decentralized. They are issued as a reward for the creation of a new block.[99]

- Anybody can create a new bitcoin address (a bitcoin counterpart of a bank account) without needing any approval.[7]:ch. 1

- Anybody can send a transaction to the network without needing any approval; the network merely confirms that the transaction is legitimate.[125]:32

Trend towards centralization

Researchers have pointed out at a « trend towards centralization ». Although bitcoin can be sent directly from user to user, in practice intermediaries are widely used.[36]:220–222 Bitcoin miners join large mining pools to minimize the variance of their income.[36]:215, 219–222[126]:3[127] Because transactions on the network are confirmed by miners, decentralization of the network requires that no single miner or mining pool obtains 51% of the hashing power, which would allow them to double-spend coins, prevent certain transactions from being verified and prevent other miners from earning income.[128] As of 2013[update] just six mining pools controlled 75% of overall bitcoin hashing power.[128] In 2014 mining pool Ghash.io obtained 51% hashing power which raised significant controversies about the safety of the network. The pool has voluntarily capped their hashing power at 39.99% and requested other pools to act responsibly for the benefit of the whole network.[129] c. 2017 over 70% of the hashing power and 90% of transactions were operating from China.[130]

According to researchers, other parts of the ecosystem are also « controlled by a small set of entities », notably the maintenance of the client software, online wallets and simplified payment verification (SPV) clients.[128]

Privacy

Bitcoin is pseudonymous, meaning that funds are not tied to real-world entities but rather bitcoin addresses. Owners of bitcoin addresses are not explicitly identified, but all transactions on the blockchain are public. In addition, transactions can be linked to individuals and companies through « idioms of use » (e.g., transactions that spend coins from multiple inputs indicate that the inputs may have a common owner) and corroborating public transaction data with known information on owners of certain addresses.[131] Additionally, bitcoin exchanges, where bitcoins are traded for traditional currencies, may be required by law to collect personal information.[132] To heighten financial privacy, a new bitcoin address can be generated for each transaction.[133]

Fungibility

Wallets and similar software technically handle all bitcoins as equivalent, establishing the basic level of fungibility. Researchers have pointed out that the history of each bitcoin is registered and publicly available in the blockchain ledger, and that some users may refuse to accept bitcoins coming from controversial transactions, which would harm bitcoin’s fungibility.[134] For example, in 2012, Mt. Gox froze accounts of users who deposited bitcoins that were known to have just been stolen.[135]

Scalability

The blocks in the blockchain were originally limited to 32 megabytes in size. The block size limit of one megabyte was introduced by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2010. Eventually the block size limit of one megabyte created problems for transaction processing, such as increasing transaction fees and delayed processing of transactions.[136] Andreas Antonopoulos has stated Lightning Network is a potential scaling solution and referred to lightning as a second layer routing network.[7]:ch. 8

Ideology

Satoshi Nakamoto stated in his white paper that: « The root problem with conventional currencies is all the trust that’s required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust. »[137]

Austrian economics

According to the European Central Bank, the decentralization of money offered by bitcoin has its theoretical roots in the Austrian school of economics, especially with Friedrich von Hayek in his book Denationalisation of Money: The Argument Refined,[138] in which Hayek advocates a complete free market in the production, distribution and management of money to end the monopoly of central banks.[139]:22

Anarchism and libertarianism

According to The New York Times, libertarians and anarchists were attracted to the idea. Early bitcoin supporter Roger Ver said: « At first, almost everyone who got involved did so for philosophical reasons. We saw bitcoin as a great idea, as a way to separate money from the state. »[137] The Economist describes bitcoin as « a techno-anarchist project to create an online version of cash, a way for people to transact without the possibility of interference from malicious governments or banks ».[140] Economist Paul Krugman argues that cryptocurrencies like bitcoin are « something of a cult » based in « paranoid fantasies » of government power.[141]

Nigel Dodd argues in The Social Life of Bitcoin that the essence of the bitcoin ideology is to remove money from social, as well as governmental, control.[143] Dodd quotes a YouTube video, with Roger Ver, Jeff Berwick, Charlie Shrem, Andreas Antonopoulos, Gavin Wood, Trace Meyer and other proponents of bitcoin reading The Declaration of Bitcoin’s Independence. The declaration includes a message of crypto-anarchism with the words: « Bitcoin is inherently anti-establishment, anti-system, and anti-state. Bitcoin undermines governments and disrupts institutions because bitcoin is fundamentally humanitarian. »[143][142]

David Golumbia says that the ideas influencing bitcoin advocates emerge from right-wing extremist movements such as the Liberty Lobby and the John Birch Society and their anti-Central Bank rhetoric, or, more recently, Ron Paul and Tea Party-style libertarianism.[144] Steve Bannon, who owns a « good stake » in bitcoin, considers it to be « disruptive populism. It takes control back from central authorities. It’s revolutionary. »[145]

A 2014 study of Google Trends data found correlations between bitcoin-related searches and ones related to computer programming and illegal activity, but not libertarianism or investment topics.[146]

Economics

Bitcoin is a digital asset designed to work in peer-to-peer transactions as a currency.[4][147] Bitcoins have three qualities useful in a currency, according to The Economist in January 2015: they are « hard to earn, limited in supply and easy to verify. »[148] Per some researchers, as of 2015[update], bitcoin functions more as a payment system than as a currency.[36]

Economists define money as serving the following three purposes: a store of value, a medium of exchange, and a unit of account.[149] According to The Economist in 2014, bitcoin functions best as a medium of exchange.[149] However, this is debated, and a 2018 assessment by The Economist stated that cryptocurrencies met none of these three criteria.[140]

Yale economist Robert J. Shiller writes that bitcoin has potential as a unit of account for measuring the relative value of goods, as with Chile’s Unidad de Fomento, but that « Bitcoin in its present form […] doesn’t really solve any sensible economic problem ».[150]

According to research by Cambridge University, between 2.9 million and 5.8 million unique users used a cryptocurrency wallet in 2017, most of them for bitcoin. The number of users has grown significantly since 2013, when there were 300,000–1.3 million users.[18]

Acceptance by merchants

The overwhelming majority of bitcoin transactions take place on a cryptocurrency exchange, rather than being used in transactions with merchants.[151] Delays processing payments through the blockchain of about ten minutes make bitcoin use very difficult in a retail setting. Prices are not usually quoted in units of bitcoin and many trades involve one, or sometimes two, conversions into conventional currencies.[36] Merchants that do accept bitcoin payments may use payment service providers to perform the conversions.[152]

In 2017 and 2018 bitcoin’s acceptance among major online retailers included only three of the top 500 U.S. online merchants, down from five in 2016.[151] Reasons for this decline include high transaction fees due to bitcoin’s scalability issues and long transaction times.[153]

Bloomberg reported that the largest 17 crypto merchant-processing services handled $69 million in June 2018, down from $411 million in September 2017. Bitcoin is « not actually usable » for retail transactions because of high costs and the inability to process chargebacks, according to Nicholas Weaver, a researcher quoted by Bloomberg. High price volatility and transaction fees make paying for small retail purchases with bitcoin impractical, according to economist Kim Grauer. However, bitcoin continues to be used for large-item purchases on sites such as Overstock.com, and for cross-border payments to freelancers and other vendors.[154]

Financial institutions

Bitcoins can be bought on digital currency exchanges.

Per researchers, « there is little sign of bitcoin use » in international remittances despite high fees charged by banks and Western Union who compete in this market.[36] The South China Morning Post, however, mentions the use of bitcoin by Hong Kong workers to transfer money home.[155]

In 2014, the National Australia Bank closed accounts of businesses with ties to bitcoin,[156] and HSBC refused to serve a hedge fund with links to bitcoin.[157] Australian banks in general have been reported as closing down bank accounts of operators of businesses involving the currency.[158]

On 10 December 2017, the Chicago Board Options Exchange started trading bitcoin futures,[159] followed by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, which started trading bitcoin futures on 17 December 2017.[160]

In September 2019 the Central Bank of Venezuela, at the request of PDVSA, ran tests to determine if bitcoin and ether could be held in central bank’s reserves. The request was motivated by oil company’s goal to pay its suppliers.[161]

As an investment

The Winklevoss twins have purchased bitcoin. In 2013, The Washington Post reported a claim that they owned 1% of all the bitcoins in existence at the time.[162]

Other methods of investment are bitcoin funds. The first regulated bitcoin fund was established in Jersey in July 2014 and approved by the Jersey Financial Services Commission.[163]

Forbes named bitcoin the best investment of 2013.[164] In 2014, Bloomberg named bitcoin one of its worst investments of the year.[165] In 2015, bitcoin topped Bloomberg’s currency tables.[166]

According to bitinfocharts.com, in 2017 there are 9,272 bitcoin wallets with more than $1 million worth of bitcoins.[167] The exact number of bitcoin millionaires is uncertain as a single person can have more than one bitcoin wallet.

Venture capital

Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund invested US$3 million in BitPay.[168] In 2012, an incubator for bitcoin-focused start-ups was founded by Adam Draper, with financing help from his father, venture capitalist Tim Draper, one of the largest bitcoin holders after winning an auction of 30,000 bitcoins,[169] at the time called « mystery buyer ».[170] The company’s goal is to fund 100 bitcoin businesses within 2–3 years with $10,000 to $20,000 for a 6% stake.[169] Investors also invest in bitcoin mining.[171] According to a 2015 study by Paolo Tasca, bitcoin startups raised almost $1 billion in three years (Q1 2012 – Q1 2015).[172]

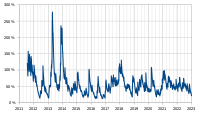

Price and volatility

The price of bitcoins has gone through cycles of appreciation and depreciation referred to by some as bubbles and busts.[173] In 2011, the value of one bitcoin rapidly rose from about US$0.30 to US$32 before returning to US$2.[174] In the latter half of 2012 and during the 2012–13 Cypriot financial crisis, the bitcoin price began to rise,[175] reaching a high of US$266 on 10 April 2013, before crashing to around US$50. On 29 November 2013, the cost of one bitcoin rose to a peak of US$1,242.[176] In 2014, the price fell sharply, and as of April remained depressed at little more than half 2013 prices. As of August 2014[update] it was under US$600.[177]

According to Mark T. Williams, as of 30 September 2014[update], bitcoin has volatility seven times greater than gold, eight times greater than the S&P 500, and 18 times greater than the US dollar.[178]

Legal status, tax and regulation

Because of bitcoin’s decentralized nature and its trading on online exchanges located in many countries, regulation of bitcoin has been difficult. However, the use of bitcoin can be criminalized, and shutting down exchanges and the peer-to-peer economy in a given country would constitute a de facto ban.[179] The legal status of bitcoin varies substantially from country to country and is still undefined or changing in many of them. Regulations and bans that apply to bitcoin probably extend to similar cryptocurrency systems.[180]

According to the Library of Congress, an « absolute ban » on trading or using cryptocurrencies applies in nine countries: Algeria, Bolivia, Egypt, Iraq, Morocco, Nepal, Pakistan, Vietnam, and the United Arab Emirates. An « implicit ban » applies in another 15 countries, which include Bahrain, Bangladesh, China, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Indonesia, Iran, Kuwait, Lesotho, Lithuania, Macau, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Taiwan.[181]

Regulatory warnings

The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission has issued four « Customer Advisories » for bitcoin and related investments.[19] A July 2018 warning emphasized that trading in any cryptocurrency is often speculative, and there is a risk of theft from hacking, and fraud.[182] In May 2014 the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission warned that investments involving bitcoin might have high rates of fraud, and that investors might be solicited on social media sites.[183] An earlier « Investor Alert » warned about the use of bitcoin in Ponzi schemes.[184]

The European Banking Authority issued a warning in 2013 focusing on the lack of regulation of bitcoin, the chance that exchanges would be hacked, the volatility of bitcoin’s price, and general fraud.[185] FINRA and the North American Securities Administrators Association have both issued investor alerts about bitcoin.[186][187]

Price manipulation investigation

An official investigation into bitcoin traders was reported in May 2018.[188] The U.S. Justice Department launched an investigation into possible price manipulation, including the techniques of spoofing and wash trades.[189][190][191]

The U.S. federal investigation was prompted by concerns of possible manipulation during futures settlement dates. The final settlement price of CME bitcoin futures is determined by prices on four exchanges, Bitstamp, Coinbase, itBit and Kraken. Following the first delivery date in January 2018, the CME requested extensive detailed trading information but several of the exchanges refused to provide it and later provided only limited data. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission then subpoenaed the data from the exchanges.[192][193]

State and provincial securities regulators, coordinated through the North American Securities Administrators Association, are investigating « bitcoin scams » and ICOs in 40 jurisdictions.[194]

Academic research published in the Journal of Monetary Economics concluded that price manipulation occurred during the Mt Gox bitcoin theft and that the market remains vulnerable to manipulation.[195] The history of hacks, fraud and theft involving bitcoin dates back to at least 2011.[196]

Research by John M. Griffin and Amin Shams in 2018 suggests that trading associated with increases in the amount of the Tether cryptocurrency and associated trading at the Bitfinex exchange account for about half of the price increase in bitcoin in late 2017.[197][198]

J.L. van der Velde, CEO of both Bitfinex and Tether, denied the claims of price manipulation: « Bitfinex nor Tether is, or has ever, engaged in any sort of market or price manipulation. Tether issuances cannot be used to prop up the price of bitcoin or any other coin/token on Bitfinex. »[199]

Criticism

The Bank for International Settlements summarized several criticisms of bitcoin in Chapter V of their 2018 annual report. The criticisms include the lack of stability in bitcoin’s price, the high energy consumption, high and variable transactions costs, the poor security and fraud at cryptocurrency exchanges, vulnerability to debasement (from forking), and the influence of miners.[200][201][202]

The Economist describes these criticisms as unfair, predominantly because the shady image may compel users to overlook the capabilities of the blockchain technology, but also due to the fact that the volatility of bitcoin is changing in time.[203]

As a speculative bubble

Bitcoin, along with other cryptocurrencies, has been described as an economic bubble by at least eight Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences laureates, including Robert Shiller,[150] Joseph Stiglitz,[204] and Richard Thaler.[205][206] Noted Keynesian economist Paul Krugman has described bitcoin as « a bubble wrapped in techno-mysticism inside a cocoon of libertarian ideology »,[141] professor Nouriel Roubini of New York University has called bitcoin the « mother of all bubbles »,[207] and University of Chicago economist James Heckman has compared it to the 17th-century tulip mania.[206]

Alan Greenspan and George Soros both referred to it as a « bubble ».[208][209] Warren Buffett called bitcoin a « mirage »

and Jamie Dimon called it a « fraud ».[210][211] Dimon’s JP Morgan later went on to launch JPM Coin.

Energy consumption

Bitcoin has been criticized for the amount of electricity consumed by mining. As of 2015[update], The Economist estimated that even if all miners used modern facilities, the combined electricity consumption would be 166.7 megawatts (1.46 terawatt-hours per year).[148]

At the end of 2017, the global bitcoin mining activity was estimated to consume between one and four gigawatts of electricity.[212] By 2018, bitcoin was estimated by Joule[213] to use 2.55 GW, while Environmental Science & Technology[214] estimated bitcoin to consume 31.29 TWh for the year (this corresponds to the use of 3.572 GW). In July 2019 BBC reported bitcoin consumes about 7 gigawatts, 0.2% of the global total, or equivalent to that of Switzerland.[215]

According to Politico, even the high-end estimates of bitcoin’s total consumption levels amount to only about 6% of the total power consumed by the global banking sector, and even if bitcoin’s consumption levels increased 100 fold from today’s levels, bitcoin’s consumption would still only amount to about 2% of global power consumption.[216]

To lower the costs, bitcoin miners have set up in places like Iceland where geothermal energy is cheap and cooling Arctic air is free.[217] Bitcoin miners are known to use hydroelectric power in Tibet, Quebec, Washington (state), and Austria to reduce electricity costs.[216][218] Miners are attracted to suppliers such as Hydro Quebec that have energy surpluses.[219] According to a University of Cambridge study, much of bitcoin mining is done in China, where electricity is subsidized by the government.[220][221]

Concerns about bitcoin’s environmental impact relate bitcoin’s energy consumption to carbon emissions.[222][223] The difficulty of translating the energy consumption into carbon emissions lies in the decentralized nature of bitcoin impeding the localization of miners to examine the electricity mix used. The results of recent studies analyzing bitcoin’s carbon footprint vary.[224][225][226][227] A study published in Nature Climate Change in 2018 claims that bitcoin « could alone produce enough CO

2 emissions to push warming above 2 °C within less than three decades. »[226] However, this analysis is subject to strong criticism as the underlying scenarios are considered as inadequate, leading to overestimations.[228][229][230] According to studies published in Joule et American Chemical Society in 2019, bitcoin’s annual energy consumption amounts to 31–45.8 TWh resulting in annual carbon emission ranging from 17[214] to 22.9 MtCO

2 which is comparable to the level of emissions of countries as Jordan and Sri Lanka or Kansas City.[227] International Energy Agency estimates bitcoin’s annual carbon emissions to be in a range from 10 to 20 MtCO

2 and characterizes the predictions in Nature Climate Change as just « sensational predictions about bitcoin » echoing the warnings from late 1990s about Internet and its increasing energy consumption.[231]

Ponzi scheme and pyramid scheme concerns

Journalists, economists, investors, and the central bank of Estonia have voiced concerns that bitcoin is a Ponzi scheme.[232][233][234][235] In April 2013, Eric Posner, a law professor at the University of Chicago, stated that « a real Ponzi scheme takes fraud; bitcoin, by contrast, seems more like a collective delusion. »[236] A July 2014 report by the World Bank concluded that bitcoin was not a deliberate Ponzi scheme.[237]:7 In June 2014, the Swiss Federal Council[238]:21 examined the concerns that bitcoin might be a pyramid scheme; it concluded that, « Since in the case of bitcoin the typical promises of profits are lacking, it cannot be assumed that bitcoin is a pyramid scheme. »

Säkerhetsproblem

Bitcoin is vulnerable to theft through phishing, scamming, and hacking. As of December 2017[update], around 980,000 bitcoins have been stolen from cryptocurrency exchanges.[91]

Use in illegal transactions

The use of bitcoin by criminals has attracted the attention of financial regulators, legislative bodies, law enforcement, and the media.[239] Bitcoin gained early notoriety for its use on the Silk Road. The U.S. Senate held a hearing on virtual currencies in November 2013.[240] The U.S. government claimed that bitcoin was used to facilitate payments related to Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections.[241]

Several news outlets have asserted that the popularity of bitcoins hinges on the ability to use them to purchase illegal goods.[147][242] Nobel-prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz says that bitcoin’s anonymity encourages money laundering and other crimes.[243][244]

In 2014, researchers at the University of Kentucky found « robust evidence that computer programming enthusiasts and illegal activity drive interest in bitcoin, and find limited or no support for political and investment motives ».[146] Australian researchers have estimated that 25% of all bitcoin users and 44% of all bitcoin transactions are associated with illegal activity as of April 2017[update]. There were an estimated 24 million bitcoin users primarily using bitcoin for illegal activity. They held $8 billion worth of bitcoin, and made 36 million transactions valued at $72 billion.[245][246]

Other critical opinions

François R. Velde, Senior Economist at the Chicago Fed, described it as « an elegant solution to the problem of creating a digital currency ».[247]

David Andolfatto, Vice President at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, stated that bitcoin is a threat to the establishment, which he argues is a good thing for the Federal Reserve System and other central banks, because it prompts these institutions to operate sound policies.[95]:33[248][249]

PayPal President David A. Marcus calls bitcoin a « great place to put assets ».[250]

In popular culture

Literature

In Charles Stross’ 2013 science fiction novel, Neptune’s Brood, the universal interstellar payment system is known as « bitcoin » and operates using cryptography.[251] Stross later blogged that the reference was intentional, saying « I wrote Neptune’s Brood in 2011. Bitcoin was obscure back then, and I figured had just enough name recognition to be a useful term for an interstellar currency: it’d clue people in that it was a networked digital currency. »[252]

Film

The 2014 documentary The Rise and Rise of Bitcoin portrays the diversity of motives behind the use of bitcoin by interviewing people who use it. These include a computer programmer and a drug dealer.[253] The 2016 documentary Banking on Bitcoin is an introduction to the beginnings of bitcoin and the ideas behind cryptocurrency today.[254]

Academia

In September 2015, the establishment of the peer-reviewed academic journal Ledger (ISSN 2379-5980) was announced. It covers studies of cryptocurrencies and related technologies, and is published by the University of Pittsburgh.[255] The journal encourages authors to digitally sign a file hash of submitted papers, which will then be timestamped into the bitcoin blockchain. Authors are also asked to include a personal bitcoin address in the first page of their papers.[256][257]

See also

anteckningar

- ^ Ordet bitcoin first occurred and was defined in the white paper[4] that was published on 31 October 2008.[10] It is a compound of the words bit et pièce de monnaie.[11]

There is no uniform convention for bitcoin capitalization. Some sources use Bitcoin, capitalized, to refer to the technology and network and bitcoin, lowercase, to refer to the unit of account.[12] The Wall Street Journal,[13] The Chronicle of Higher Education,[14] et cela Oxford English Dictionary[11] advocate use of lowercase bitcoin in all cases, a convention followed throughout this article.

- ^ As of 2014[update], BTC is a commonly used code.[77] It does not conform to ISO 4217 as BT is the country code of Bhutan, and ISO 4217 requires the first letter used in global commodities to be ‘X’.

- ^ As of 2014[update], XBT, a code that conforms to ISO 4217 though is not officially part of it, is used by Bloomberg L.P.,[78] CNNMoney,[79] and xe.com.[80]

- ^ The genesis block is the block number 0. The timestamp of the block is 2009-01-03 18:15:05. This block is unlike all other blocks in that it does not have a previous block to reference.

- ^ Relative mining difficulty is defined as the ratio of the difficulty target on 9 January 2009 to the current difficulty target.

- ^ It is misleading to think that there is an analogy between gold mining and bitcoin mining. The fact is that gold miners are rewarded for producing gold, while bitcoin miners are not rewarded for producing bitcoins; they are rewarded for their record-keeping services.[95]

- ^ The exact number is 20,999,999.9769 bitcoins.[7]:ch. 8

- ^ The private key can be printed as a series of letters and numbers, a seed phrase, or a 2D barcode. Usually, the public key or bitcoin address is also printed, so that a holder of a paper wallet can check or add funds without exposing the private key to a device.

- ^ Liquidity is estimated by a 365-day running sum of transaction outputs in USD.

- ^ The price of 1 bitcoin in US dollars.

References

- ^ en b « Unicode 10.0.0 ». Unicode Consortium. 20 June 2017. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ en b Jason Mick (12 June 2011). « Cracking the Bitcoin: Digging Into a $131M USD Virtual Currency ». Daily Tech. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ « Releases – bitcoin/bitcoin ». Retrieved 9 March 2020 – via GitHub.

- ^ en b c d e f Nakamoto, Satoshi (31 October 2008). « Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System » (PDF). bitcoin.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ Nakamoto; et al. (1 April 2016). « Bitcoin source code – amount constraints ». Archived from the original on 1 July 2018.

- ^ Kettley, Sebastian (21 December 2017). « Bitcoin price: How many bitcoin are there and when will the popular crypto token run out? ». Daily Express. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ en b c d e f g h jag j k l m n O p q r s t u v w Antonopoulos, Andreas M. (April 2014). Mastering Bitcoin: Unlocking Digital Crypto-Currencies. O’Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1-4493-7404-4.

- ^ en b c d e « Statement of Jennifer Shasky Calvery, Director Financial Crimes Enforcement Network United States Department of the Treasury Before the United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Subcommittee on National Security and International Trade and Finance Subcommittee on Economic Policy » (PDF). fincen.gov. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. 19 November 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ Empson, Rip (28 March 2013). « Bitcoin: How an Unregulated, Decentralized Virtual Currency Just Became a Billion Dollar Market ». TechCrunch. AOL inc. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ Vigna, Paul; Casey, Michael J. (January 2015). The Age of Cryptocurrency: How Bitcoin and Digital Money Are Challenging the Global Economic Order (1 ed.). New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-1-250-06563-6.

- ^ en b « bitcoin ». OxfordDictionaries.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ Bustillos, Maria (2 April 2013). « The Bitcoin Boom ». The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

Standards vary, but there seems to be a consensus forming around Bitcoin, capitalized, for the system, the software, and the network it runs on, and bitcoin, lowercase, for the currency itself.

- ^ Vigna, Paul (3 March 2014). « BitBeat: Is It Bitcoin, or bitcoin? The Orthography of the Cryptography ». WSJ. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ Metcalf, Allan (14 April 2014). « The latest style ». Lingua Franca blog. The Chronicle of Higher Education (chronicle.com). Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ en b S., L. (2 November 2015). « Who is Satoshi Nakamoto? ». The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ en b c d e Davis, Joshua (10 October 2011). « The Crypto-Currency: Bitcoin and its mysterious inventor ». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 31 oktober 2014.

- ^ « What is Bitcoin? ». CNN Money. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ^ en b Hileman, Garrick; Rauchs, Michel. « Global Cryptocurrency Benchmarking Study » (PDF). Cambridge University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 April 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^ en b « Bitcoin ». NOUS. Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ « SEC.gov | INVESTOR ALERT: BITCOIN AND OTHER VIRTUAL CURRENCY-RELATED INVESTMENTS ». www.sec.gov. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ Bernard, Zoë (2 December 2017). « Everything you need to know about Bitcoin, its mysterious origins, and the many alleged identities of its creator ». Business Insider. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ^ Finley, Klint (31 October 2018). « After 10 Years, Bitcoin Has Changed Everything—And Nothing ». Wired. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- ^ Nakamoto, Satoshi (3 January 2009). « Bitcoin ». Archived from the original on 21 July 2017.

- ^ Nakamoto, Satoshi (9 January 2009). « Bitcoin v0.1 released ». Archived from the original on 26 March 2014.

- ^ en b Wallace, Benjamin (23 November 2011). « The Rise and Fall of Bitcoin ». Wired. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ « Block 0 – Bitcoin Block Explorer ». Archived from the original on 15 October 2013.

- ^ Pagliery, Jose (2014). Bitcoin: And the Future of Money. Triumph Books. ISBN 9781629370361. Archived from the original on 21 January 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ « Here’s The Problem with the New Theory That A Japanese Math Professor Is The Inventor of Bitcoin ». San Francisco Chronicle. 19 May 2013. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ Peterson, Andrea (3 January 2014). « Hal Finney received the first Bitcoin transaction. Here’s how he describes it ». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015.

- ^ Popper, Nathaniel (30 August 2014). « Hal Finney, Cryptographer and Bitcoin Pioneer, Dies at 58 ». NYTimes. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^ Kharpal, Arjun (18 June 2018). « Everything you need to know about the blockchain ». CNBC. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ McMillan, Robert. « Who Owns the World’s Biggest Bitcoin Wallet? The FBI ». Wired. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ Simonite, Tom. « Meet Gavin Andresen, the most powerful person in the world of Bitcoin ». MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ en b Odell, Matt (21 September 2015). « A Solution To Bitcoin’s Governance Problem ». TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ en b Vigna, Paul (17 January 2016). « Is Bitcoin Breaking Up? ». The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ en b c d e f g h Rainer Böhme; Nicolas Christin; Benjamin Edelman; Tyler Moore (2015). « Bitcoin: Economics, Technology, and Governance ». Journal of Economic Perspectives. 29 (2): 213–238. doi:10.1257/jep.29.2.213.

- ^ en b c d e f « Bitcoin Historical Prices ». OfficialData.org. Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ « Ex-Googler Gives the World a Better Bitcoin ». WIRED. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ^ Yang, Stephanie (31 January 2018). « Want to Keep Up With Bitcoin Enthusiasts? Learn the Lingo ». WSJ. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ en b c d French, Sally (9 February 2017). « Here’s proof that this bitcoin crash is far from the worst the cryptocurrency has seen ». Market Watch. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ Bustillos, Maria (1 April 2013). « The Bitcoin Boom ». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ en b Lee, Timothy (11 March 2013). « Major glitch in Bitcoin network sparks sell-off; price temporarily falls 23% ». arstechnica.com. Archived from the original on 22 April 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Blagdon, Jeff (12 March 2013). « Technical problems cause Bitcoin to plummet from record high, Mt. Gox suspends deposits ». The Verge. Archived from the original on 22 April 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ « Bitcoin Charts ». Archived from the original on 9 May 2014.

- ^ Lee, Timothy (20 March 2013). « US regulator Bitcoin Exchanges Must Comply With Money Laundering Laws ». Arstechnica. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

Bitcoin miners must also register if they trade in their earnings for dollars.

- ^ « Application of FinCEN’s Regulations to Persons Administering, Exchanging, or Using Virtual Currencies » (PDF). Department of the Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ Roose, Kevin (8 April 2013) « Inside the Bitcoin Bubble: BitInstant’s CEO – Daily Intelligencer ». Archived from the original on 9 April 2014.. Nymag.com. Retrieved on 20 April 2013.

- ^ « Bitcoin Exchange Rate ». Bitcoinscharts.com. Archived from the original on 24 June 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ Dillet, Romain. « Feds Seize Assets From Mt. Gox’s Dwolla Account, Accuse It Of Violating Money Transfer Regulations ». Archived from the original on 9 October 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Berson, Susan A. (2013). « Some basic rules for using ‘bitcoin’ as virtual money ». American Bar Association. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ Sampson, Tim (2013). « U.S. government makes its first-ever Bitcoin seizure ». The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ en b Ember, Sydney (2 July 2014). « Winner of Bitcoin Auction, Tim Draper, Plans to Expand Currency’s Use ». The New York Times DealBook. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ « After Silk Road seizure, FBI Bitcoin wallet identified and pranked ». Archived from the original on 5 April 2014.

- ^ « Silkroad Seized Coins ». Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ Hill, Kashmir. « The FBI’s Plan For The Millions Worth Of Bitcoins Seized From Silk Road ». Forbes. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014.

- ^ Kelion, Leo (18 December 2013). « Bitcoin sinks after China restricts yuan exchanges ». bbc.com. BBC. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ « China bans banks from bitcoin transactions ». The Sydney Morning Herald. Reuters. 6 December 2013. Archived from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 31 oktober 2014.

- ^ « Baidu Stops Accepting Bitcoins After China Ban ». Bloomberg. New York. 7 December 2013. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 11 december 2013.

- ^ « China bars use of virtual money for trading in real goods ». English.mofcom.gov.cn. 29 June 2009. Archived from the original on 29 November 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ Rayman, Noah (30 July 2014). « You Can Now Donate to Wikipedia in Bitcoin ». TIME. Archived from the original on 30 July 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ en b c Vigna, Paul (21 July 2017). « Bitcoin Rallies Sharply After Vote Resolves Bitter Scaling Debate ». WSJ. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ « Bitcoin Hits a New Record High, But Stops Short of $20,000 ». Fortune. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ « RMB Bitcoin trading falls below 1 pct of world total ». Xinhuanet. Xinhua. 7 July 2018. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 10 juli 2018.

- ^ en b « Bitcoin USD ». Yahoo Finance!. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ Dawkins, David (10 July 2018). « Has CHINA burst the bitcoin BUBBLE? Trading in RMB drops from 90% to 1% ». Express. Retrieved 10 juli 2018.

- ^ « Bitcoin turns 10: The obscure technology that became a household name ». CNBC. 4 January 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ Chavez-Dreyfuss, Gertrude (3 July 2018). « Cryptocurrency exchange theft surges in first half of 2018: report ». Reuters. Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 10 juli 2018.

- ^ « Cryptocurrencies Tumble After $32 Million South Korea Exchange Hack ». Fortune. Bloomberg. 20 July 2018. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 10 juli 2018.

- ^ Shane, Daniel (11 June 2018). « Billions in cryptocurrency wealth wiped out after hack ». CNN. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 10 juli 2018.

- ^ Russell, Jon (10 July 2018). « The crypto world’s latest hack sees Israel’s Bancor lose $23.5M ». TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 10 juli 2018.

- ^ Osipovich, Alexander (22 September 2019). « NYSE Owner Launches Long-Awaited Bitcoin Futures ». WSJ. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Olga Kharif (24 October 2019). « Bakkt Plans First Regulated Options Contracts on Bitcoin Futures ». bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ « YouTube admits error over Bitcoin video purge ». bbc.com. BBC. 28 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Alexander, Doug (4 February 2019). « Crypto CEO Dies Holding Only Passwords That Can Unlock Millions in Customer Coins ». bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ en b c del Castillo, Michael (19 March 2020). « Bitcoin’s Magic Is Fading, And That’s A Good Thing ». Forbes.com. Forbes. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ Dellinger, A. J. (15 February 2018). « What Are Cryptocurrency Ticker Symbols? BTC, XRP, ETH And More Explained ». International Business Times. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ Romain Dillet (9 August 2013). « Bitcoin Ticker Available On Bloomberg Terminal For Employees ». TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ « Bitcoin Composite Quote (XBT) ». CNN Money. CNN. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ « XBT – Bitcoin ». xe.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ « Regulation of Bitcoin in Selected Jurisdictions » (PDF). The Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Center. January 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ Katie Pisa & Natasha Maguder (9 July 2014). « Bitcoin your way to a double espresso ». cnn.com. CNN. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ en b « Blockchair ». Blockchair.com. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ en b c d e « Charts ». Blockchain.info. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ en b c d e f « The great chain of being sure about things ». The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. 31 October 2015. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ Sparkes, Matthew (9 June 2014). « The coming digital anarchy ». The Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ en b c d e Joshua A. Kroll; Ian C. Davey; Edward W. Felten (11–12 June 2013). « The Economics of Bitcoin Mining, or Bitcoin in the Presence of Adversaries » (PDF). The Twelfth Workshop on the Economics of Information Security (WEIS 2013). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

A transaction fee is like a tip or gratuity left for the miner.

- ^ « Man Throws Away 7,500 Bitcoins, Now Worth $7.5 Million ». CBS DC. 29 November 2013. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ Krause, Elliott (5 July 2018). « A Fifth of All Bitcoin Is Missing. These Crypto Hunters Can Help ». Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ^ Jeffries, Adrianne (19 December 2013). « How to steal Bitcoin in three easy steps ». The Verge. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ en b Harney, Alexandra; Stecklow, Steve (16 November 2017). « Twice burned – How Mt. Gox’s bitcoin customers could lose again ». Reuters. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ Martindale, Jon (16 March 2018). « Who owns all the Bitcoin? A few billionaire whales in a small pond ». Digital Trends. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ « Bitcoin mania is hurting PC gamers by pushing up GPU prices ». Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ « Cryptocurrency mining operation launched by Iron Bridge Resources ». World Oil. 26 January 2018. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018.

- ^ en b Andolfatto, David (31 March 2014). « Bitcoin and Beyond: The Possibilities and Pitfalls of Virtual Currencies » (PDF). Dialogue with the Fed. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ Sherman, Alan; Javani, Farid; Golaszewski, Enis (25 March 2019). « On the Origins and Variations of Blockchain Technologies ». IEEE Security and Policy. 17 (1): 72–77. arXiv:1810.06130. doi:10.1109/MSEC.2019.2893730.

- ^ « Difficulty History » (The ratio of all hashes over valid hashes is D x 4,295,032,833, where D is the published « Difficulty » figure.). Blockchain.info. Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ Hampton, Nikolai (5 September 2016). « Understanding the blockchain hype: Why much of it is nothing more than snake oil and spin ». Computerworld. IDG. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ en b Ashlee Vance (14 November 2013). « 2014 Outlook: Bitcoin Mining Chips, a High-Tech Arms Race ». Businessweek. Archived from the original on 21 November 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ « Block #420000 ». Blockchain.info. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ Ritchie S. King; Sam Williams; David Yanofsky (17 December 2013). « By reading this article, you’re mining bitcoins ». qz.com. Atlantic Media Co. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Shin, Laura (24 May 2016). « Bitcoin Production Will Drop By Half In July, How Will That Affect The Price? ». Forbes. Archived from the original on 24 May 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Biggs, John (8 April 2013). « How To Mine Bitcoins ». Techcrunch. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017.

- ^ Adam Serwer & Dana Liebelson (10 April 2013). « Bitcoin, Explained ». motherjones.com. Mother Jones. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ « Bitcoin: Bitcoin under pressure ». The Economist. 30 November 2013. Archived from the original on 30 November 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ « Blockchain Size ». Blockchain.info. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ Gervais, Arthur; O. Karame, Ghassan; Gruber, Damian; Capkun, Srdjan. « On the Privacy Provisions of Bloom Filters in Lightweight Bitcoin Clients » (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ^ Bill Barhydt (4 June 2014). « 3 reasons Wall Street can’t stay away from bitcoin ». NBCUniversal. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ « MtGox gives bankruptcy details ». bbc.com. BBC. 4 March 2014. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ en b Barski, Conrad; Wilmer, Chris (2015). Bitcoin for the Befuddled. No Starch Press. ISBN 978-1-59327-573-0.

- ^ Popper, Nathaniel (19 December 2017). « How the Winklevoss Twins Found Vindication in a Bitcoin Fortune ». The New York Times. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ Alexander, Doug (15 February 2019). « Quadriga’s late founder used to store clients’ Bitcoin passwords on paper so they wouldn’t get lost ». Bloomberg News. Financial Post. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ en b Staff, Verge (13 December 2013). « Casascius, maker of shiny physical bitcoins, shut down by Treasury Department ». The Verge. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ en b c d e Ahonen, Elias; Rippon, Matthew J.; Kesselman, Howard (15 April 2016). Encyclopedia of Physical Bitcoins and Crypto-Currencies. ISBN 978-0-9950-8990-7.

- ^ Mack, Eric (25 October 2011). « Are physical Bitcoins legal? ». CNET. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ British Museum (2012). « Bitcoin token with digital code for bitcoin currency ». Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ Roberts, Daniel (15 December 2017). « How to send bitcoin to a hardware wallet ». Yahoo Finance. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ Skudnov, Rostislav (2012). Bitcoin Clients (PDF) (Bachelor’s Thesis). Turku University of Applied Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ « Bitcoin Core version 0.9.0 released ». bitcoin.org. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ Metz, Cade (19 August 2015). « The Bitcoin Schism Shows the Genius of Open Source ». Wired. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ Allison, Ian (28 April 2017). « Ethereum co-founder Dr Gavin Wood and company release Parity Bitcoin ». International Business Times. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ Selena Larson (1 August 2017). « Bitcoin split in two, here’s what that means ». CNN Tech. Cable News Network. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ « Bitcoin Gold, the latest Bitcoin fork, explained ». Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Meola, Andrew (5 October 2017). « How distributed ledger technology will change the way the world works ». Business Insider. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ Jerry Brito & Andrea Castillo (2013). « Bitcoin: A Primer for Policymakers » (PDF). Mercatus Center. George Mason University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.